Meet the little moments within Kruger National Park that reminded me of the beautiful harmony rangers and park staff are fighting so hard to protect.

In this beautiful and complex world, things can get pretty dark if you let that first shadowy moment start to seep in. My time in South Africa reporting on the rhino poaching crisis was no exception. Days filled with the stories of men and women fighting what is beyond an uphill battle to protect rhino against the illicit trade in horn can very easily slip ones mind down that road to darkness if you let it. But the little moments—like a perfectly-timed stop in Kruger alongside a duo of vibrant white-fronted bee eaters—remind you of the beautiful harmony these rangers and staff are fighting to protect, and have also retained a deep passion for.

Among the corruption in this country which also has roots deep within the police system, judicial system, and even now within the individuals tasked with protecting wildlife due to syndicate tactics, there is still a handful—a true core—of passionate individuals who continue to fight this war 24/7, with integrity, and positivity. Their dedication and ability to withstand is inspiring. This is not only a rhino story. It is so deeply a human story, and a story entwined ultimately with every other species on the planet.

Meet the individuals in South Africa’s Greater Kruger Ecosystem whose boots on the ground efforts land them shouldering the immense weight of protecting wild rhinos for the world

The largest remaining population of wild rhinoceros left in the world reside in Kruger National Park, traversing the park itself as well as the surrounding private reserves that make up the Greater Kruger ecosystem. But being a home for rhinos comes with the intense pressure of being a poaching hotspot. Rangers of Kruger National Park and its surrounding private reserves shoulder the immense responsibility to protect this species from ever-manipulative syndicate tactics. Journey into a ranger’s world through this collection of photographs made while on patrol with several private Anti-Poaching Units in the Greater Kruger ecosystem. The rangers featured in this photography series felt comfortable being photographed in their roles. This initial trip and the stories shared with me by the rangers below helped shape the NGS-funded grant I was awarded in 2019 to return to Kruger and cover this story in depth. If you keep scrolling, you can read my reflections for the photographs created in 2018 as I began to understand the true challenges humans—both rangers and poachers—face fueling the poaching crisis.

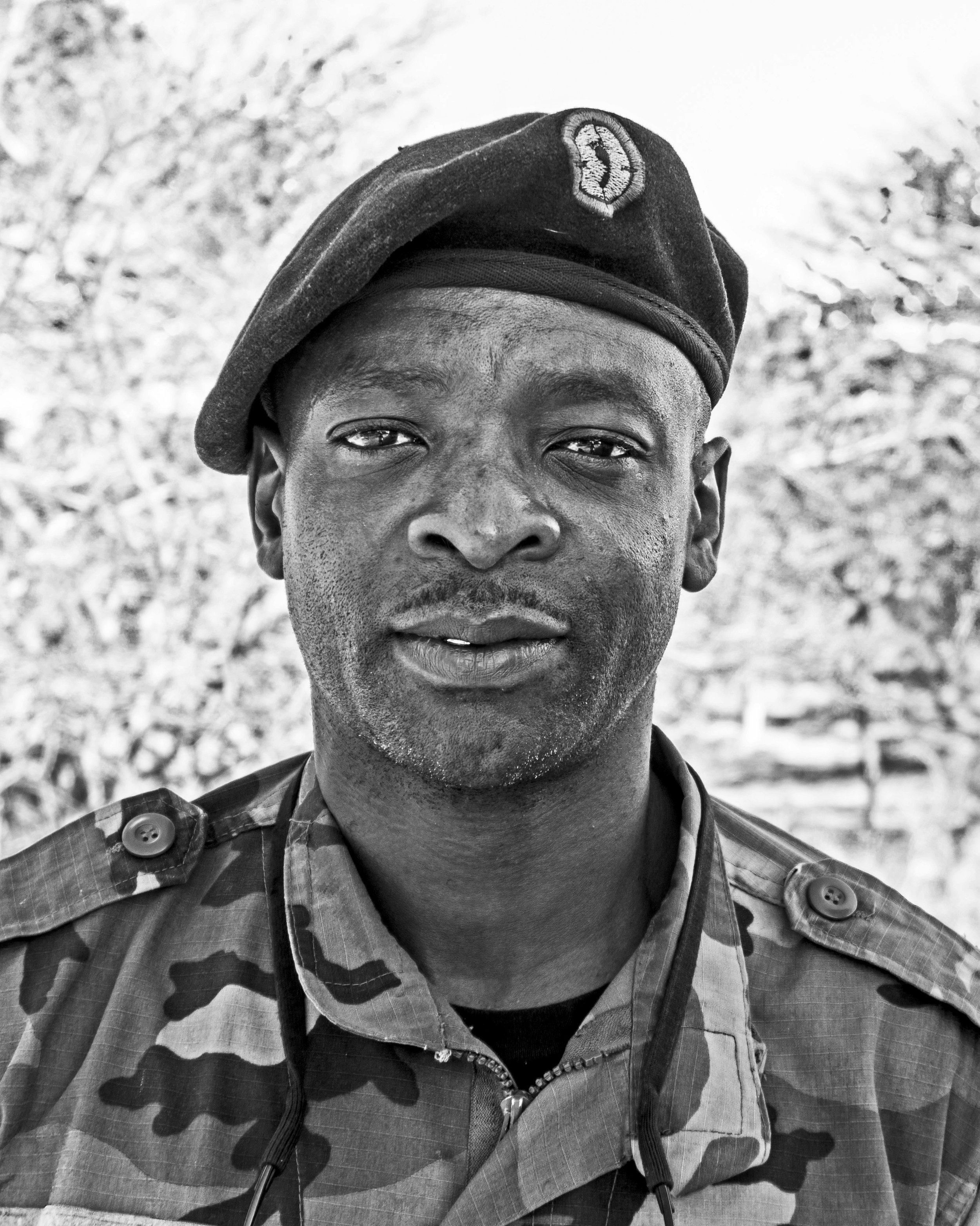

“I MUST SAVE THESE ANIMALS BECAUSE THEY CAN’T FIGHT FOR THEMSELVES...

...Some people they pay a lot of money, but me as an anti-poacher, I live with the animals. I love this place, I love the bush. I feel like now it’s my home.”

- Pilani, anti-poacher for 18 years.

I have never met anyone who knows his own environment quite like this man and his fellow anti-poachers. These guys have an understanding of the South African bush that is initially hard to wrap one’s head around. They are arguably some of the best trackers around, being able to identify a poacher’s intentions and plan simply from the spoor (tracks) they are following.

From the conversations I’ve had in the past two days, it has become apparent that these men have a tie to wildlife that runs deep and drives them to put their lives on the line every day and night to protect their land’s natural heritage.

The guys in this unit who have that connection view it as a lifestyle—a sense of belonging to a brotherhood, where they work in unity to protect what they love.

This shot was taken tonight while heading out on night patrol just before sunset. It has been incredible getting to know the anti-poachers of this unit, and I look forward to the day I’m able to share their story in greater detail.

JOSH, 20 YEARS OLD

I have a series of portraits taken of Josh just after my interview with him. In every single one of them he is proudly featuring his M4 front and center, paired with a hardened expression and the slightest hint of a smirk. All except this one.

I loved being able to capture a genuine smile and shyness that reflects the passionate wildlife-lover I interviewed 1,000 times better than his forced pose.

Josh entered an intense 6-week anti-poaching training course at 18 years old and has been deployed ever since. He is incredibly proud of the work he’s doing, and of the brothers he has alongside him in the bush.

This image serves as a glimpse into the softer side of APU rangers that was so refreshing to see. It is easy for the public to see only one side of these guys—the the guys we know are out there “hunting poachers.” However, this media-driven idea that anti-poaching units are deploying rangers with the goal of catching poachers, dead or alive, is a dangerous one; and focusing on the idea that these men live in the cross-fire of a war against poachers is a dangerous road.

In the wake of a dead poacher are 10 more already heading into the bush. In the wake of a dead poacher is a complete loss of potential intelligence that one life held, a complete loss of potential reformation, and a family left devastated—a father, an uncle, a son, a fellow human being, gone. Glorifying a war against poachers won’t promote progress. The poachers aren’t the enemy. The enemy is the root cause of why these poachers have turned to killing wildlife as a source of income. It’s the demand overseas and other socioeconomic issues that are driving the crisis.

“THIS IS THE ANIMAL THAT I HAVE BEEN SEARCHING FOR.”

- Thabani K., a Rhino Task Team anti-poaching ranger, recalls his immediate reaction to the first time he encountered a poacher in the bush.

Thabani was the first APU ranger that I interacted with in South Africa, and has remained one of the most memorable. He feels at home in the bush, among the wildlife. Wildlife is predictable and easy for him to read and respect. It is the people, the poachers, who are the animals in his eyes.

While Thabani’s connection to the African bush runs deep, he made it clear that he did not grow up that way. He put it quite simply to me: “In most communities, even now, if one were to show a young impala to a black child and a white child, the white child would want to keep it and care for it, while the black child would want to kill it.” Growing up, wildlife ownership was tied to white landowners (and in most cases, still is). Therefore, his community and the majority of those who live in the areas surrounding the reserves of The Greater Kruger National Park do not see the direct value or benefit of wildlife.

Now, Thabani is dedicating his life to protecting not just rhino, but all wildlife on these reserves, including impala because he wants to ensure his children grow up with the understanding and opportunity to see this wildlife as a core part of their heritage.

While Thabani was quick to inform me of his gratitude for all the individuals who are coming to South Africa to help make a difference, he also reminded me of one thing: his frustration. He sees foreigners valuing African wildlife more than his fellow Africans do. Instead, he hopes that future generations will take pride in wildlife as an integral part of who they are as citizens of Africa.

MORNING BORDER PATROL WITH THE BLACK MAMBAS

What did I find here? A 5:00am wake-up call, intense African heat, laughter and chats about boyfriends, babies, and big dreams to see NYC. These women are boots on the ground, but represent an entirely different approach to anti-poaching.

What was missing? Weapons of any kind.

In an environment of heavily para-militarized anti-poaching units, the Black Mambas take on a new philosophy when it comes to combating the poaching crisis in South Africa. Women in head-to-toe camouflage often conjures the glorified and media- driven idea of G.I. Janes heading out into the bush to stop poachers in their tracks. Craig Spencer, Warden of Balule, founder of Transfrontier Africa, and the man behind the Black Mambas APU, is quick to voice his disappointment with such depictions.

The mission of these women is not to catch poachers. They are here on the Balule Nature Reserve to prevent poaching through early detection.

Border patrols like this one help detect potential entry points and disturbances along the fencing, as well as spoor indicating possible incursion.

The philosophy behind the Black Mambas is one aimed to change the attitude of communities toward wildlife. The 31 women who comprise this anti-poaching unit are mothers, role models, and peer educators for their communities.

The success of the Black Mambas is not measured in the number of poachers caught, but by the number of weeks free of poaching incidents across the land they cover.

AT 6:00 P.M. SHARP, I pile into a white pick-up truck.

Three Black Mambas, all siblings, hop in with me. I’m alongside two sisters and their brother Collen, one of the original Black Mambas and one of only two males in the entire unit.

We are on night patrol.

The sun is sinking as we start our drive throughout the reserve. As darkness creeps in, we stop the vehicle for OP (observation post). We sit, and we listen. The air is still heavy and hot from the day, and roars of a lion pride echo towards us from deep within Balule.

We have one main goal tonight: be the diligent presence in the reserve for early detection against poachers.

The eyes of this well-trained trio are scanning fence lines, road edges, and watering holes. They are searching for any sign of spoor or disturbance to report back to the ops room. When spoor is found, the Mambas exit the relative safety of the pick- up into the African bush to track and determine if the tracks are from a potential poacher, and I go with them.

The Black Mambas take immense risks, from the inevitable interactions with the hidden yet omnipresent wildlife, to potential unarmed run-ins with poachers. Yet they take it all in stride with a level head and deep sense of pride.

They are quick to tell me that they could die any day—from a car crash, from a fire, from anything in any other job. So why would they hesitate to be out here protecting what they love, making a difference for wildlife and their communities?

WE ARE TRACKING RHINO.

Peter Wearne, unit manager for the Makalali K9 Conservation team, sees the sun rise every day.

He’s up at 3:00, no later, to begin tracking the black and white rhino on his closed-system reserve. Peter has two men on patrol with him, one pictured here at 4:33am reading the telemetry location of a female white rhino and her calf.

Shortly afterward we set off into the bush to track on foot and confirm the health and location of both rhinos.

The K9 Conservation team knows the location of every rhino on the reserve, confirmed daily to best protect the population from poachers and so Wearne can best strategize patrols based on potential entry hotspots.

Wearne reminds me that things have been quiet on the reserve lately. He attributes that to his dogs and the huge amount of work that he and his team have put into making this expanse of land a place poachers have no shot at breaching.

I’M SURROUNDED BY DOGS

As we head off into the bush, storm brewing in the background.

Three Belgian Malinois, two red tick coon hounds, and a massive slate grey Weimeraner run ahead.

A distinct, long whistle from the lips of Peter Wearne, K9 Conservation unit manager, keeps the attention of his pack. It has been a hellish day of intense heat and the pups are finally getting a walk in.

Wearne picks up a stone, rolls it in his hand, and lets it fly into the brush. The two Malinois do not hesitate to sprint in pursuit.

Moments later the exact same rock is returned to Wearne’s hand.

These are the canines protecting Makalali Game Reserve’s white and black rhino.

Tomorrow we head out at 4:00 a.m. to track. Tonight’s walk was just a tiny preview of what Wearne’s pack is capable of.

A GLIMPSE OF HOPE among the tragedy our own species is responsible for.

These orphaned baby rhinos are sweet, charismatic, individuals. They also have a dark past full of trauma, which they will struggle with the rest of their lives.

Each of these babies has lost their mother at the hands of poachers, even facing the near-fatal swings of a machete, or pack of hungry hyenas who had come to feed on their mother’s body while they still tried to suckle milk.

The heart-wrenching stories of these little ones should serve as a wake-up call for all of us. They are less than three years old, yet have already endured so very much.

The focus here at this rhino sanctuary is to save and rehab every orphaned rhino, and to be a stronghold for successful release.

The survival of rhinos and the perpetuation of the trade in their horn is something we all have on our shoulders as human beings, collectively. Though we may not be directly involved as the poacher or consumer, each of us has the potential to make a difference, so long as we put in the effort to be well-informed regarding this illicit trade and the countries, communities, and cultures involved.

The issue is complex, and the solution will not be simple. However, perhaps we should choose to view this complexity as something that emphasizes the importance of awareness on all fronts—not just awareness of the species in threat. Let’s put the effort in to take that to heart. At the very least, we owe these orphans that.

THREE WHITE RHINO CALVES,

all under three years old, all who’ve lost their mothers to poaching, all with numerous trauma-induced issues to cope with for the rest of their lives.

I’ve focused so much on the human side of this anti-poaching story, but my emotions are raw for these little ones.

Each orphaned rhino has an array of problems associated with the trauma they endured while witnessing the killing of their mother.

Some have digestive issues linked to stressors, no matter how small. Some have physical wounds that have taken time to heal, from machete attacks in a failed poaching attempt, or encounters with predators while staying beside their dead mother. Though the wounds have had time to scar over, the effects are long-lasting.

On top of the staff and volunteers at Care For Wild Rhino Sanctuary who meticulously care for these orphans, these little ones have another group of watchful eyes looking over them.

The anti-poaching initiatives of a sanctuary of this size require high-level security and attention with broad intelligence networks and collaboration.

Multiple styles of anti-poaching techniques are implemented in order to ensure that none of these rhinos will have to endure the tremendously horrific event of poaching twice.

INFORMANTS AND INSIDE JOBS

For anti-poaching initiatives, a unified unit of rangers is of utmost importance, as well as a strongly built and maintained intelligence network.

Why? Inside jobs.

If one thing has become clear over the course of this past month, it’s that the majority of poaching is a result of informants. Who are these informants? People from the inside. I’ll explain.

Let’s lay out the landscapes on which these anti-poaching units operate. In The Greater Kruger National Park, land is dividedinto both partially open and also closed systems which are the property of landowners. I won’t get into the nitty-gritty, but essentially as long as the property has adequate protective fencing, the wildlife on their property is theirs and it is up to them to manage it how they see fit. Some of these areas are entirely fenced in, like many of the smaller game reserves in the region, while others are partially fenced, still open into the much greater Kruger. There is a mix of reserves in which wildlife populations are either migrating, or consistently in one place, with a lot of people deciding what to do with their wildlife separately from one another, including how to protect it.

Now let’s think of all the people involved on these pieces of land, large or small.

On each of these reserves, there is at least one eco-tourism operation. These lodges have countless employees, including field guides trained to take guests on safari and who are in the know when it comes to game location. They know where the rhino are.

These reserves also have landowners with holiday homes or small farms, where even if they aren’t there year-round, staff is. This staff typically is not making much money, and also have a familiarity with the bush and whereabouts of the wildlife on the reserve.

There are also reserve staff, such as gate operators (sometimes associated with a security operation that also provides anti-poaching, but not always).There are also the anti- poaching and security units operating on that land

Informants can come from all of these angles.

Think about it: a game ranger or field guide who makes less than minimum wage gets talking to the wrong person. That person tells him, I’ll give you R14,000 if you tell me where the rhino are on the property. Thats around $1,150 USD. That’s a hell of a lot of money for a phone call. Minimal involvement and relatively low risk, with a high reward. And that’s just one scenario of many. In order to combat this, employers of lodges and safaris actively test their staff with polygraphs to make sure they are not involved with poaching or with syndicates.Anti-poaching units are doing the same. Trust is very fragile within this industry. Many of the APUs I have spent time with believe that the intensity of their training process is one of the best ways to build such trust and weed out those who are not dedicated to this tough position.

THIS IS CHARLIE ROMEO

He has been a specialized field ranger for the NKWE Project: Save The Rhino since its inception in 2013. He is one of two starting rangers that have become the head of the academy’s go-to men, earning him the phonetic alphabet naming I came to know him as. Rood seems to use this naming favorably with select individuals including these two, and now with me. I have been Tango Kilo for the week.

Charlie Romeo is also the dog handler for the unit, responsible for training Hunter, a Belgian malinois-german shepherd mix in spoor tracking and attack tactics.

I went on a tracking exercise with him and another ranger, and it was a first-hand look at the strenuous work these rangers handle with ease, accredited to their intense and continuous military-style training.

We spent the morning running through the bush as Hunter, nose to the ground, followed the pre-laid spoor. It was amazing to see the teamwork between the two. Dogs have speed and a keen sense of smell that even the best-trained ranger lacks, but a canine is only as good as the tracking ability of the ranger he’s paired with. This is why Charlie Romeo is the only ranger in command of Hunter. They have trained together, which is a key factor in making them a stellar team.

TRACKING RHINO: IN THE POACHERS SHOES

The emotions behind this photograph are stronger than anything I could ever capture. We approached this pair of female white rhinos on foot, an interaction which changed everything for me.

I saw how easy it is to walk up on these beautiful animals so long as you understand them, their behaviors, and their senses. Approach slowly, and check the wind. Make sure it is in your favor, and keep yourself in the shade where they will have a more difficult time placing you with their poor eyesight. This will keep them most relaxed while you spend time with them. Listening to them breathe, watching them sway. It’s a beautiful, peaceful, and incredible moment to experience in that shared space with two giants.

What left me with such a twist in my stomach was putting myself in another person’s shoes: a local short on cash, maybe with hungry mouths to feed in a society where the unemployment rate is reaching 40%, but also maybe just trying to keep up with his neighbors as they grow their wealth through illegal means.

I’m in the shoes of a poacher from a rural community who has known the bush his whole life. He knows that rhino and how to track it. He knows how to sneak in undetected, with one goal in mind.

Get the horn.

Per kilo, it’s worth more than gold.

This is what we all need to try and understand. Put the small effort in. Why is that person turning to poaching as his solution? Why is that person turning to brutally killing another living being as his solution? Poaching is a socioeconomic issue that runs deep, and we cannot make a dent in the poaching crisis without understanding the motivations behind the killing.

AN AERIAL PERSPECTIVE

Along with altitude, a new perspective was gained this evening, and I’m feeling quite fortunate to have seen this part of South Africa from a new vantage point while learning of its struggles and the reasons behind them.

Tomorrow morning, I’m heading out with the 14 men from HQ on an overnight deployment.

These men will be protecting rhino and other wildlife on private reserves in the area. Many landowners have had a huge desire for rhino in the past, but as the security risk of rhino only continues to increase with the poaching crisis, more and more landowners are selling rhino off their property.

Currently there are no legal requirements for a landowner to have rhino on his or her property. In other words, a landowner may farm rhino even when they have no means for adequate security to protect the species.

Here lies a huge issue for the rhino of the Waterburg area, where many rhinos have been lost due to negligence and lack of proper security in this high- risk environment.

NKWE OVERNIGHT DEPLOYMENT OPERATION

These photos are some of my favorite from the overnight deployment of NKWE rangers. Why?

Because here you see seven guys, all in their civies. At a glance, they could be any group of guys hanging on the back of a truck. The truth? Quite simply, they’re not.

In uniform, these men are specialized rangers who have gone through years of rigorous training and re-training for one very focused purpose: saving rhino.

I loved seeing this side of the rangers compared to the serious focus they exhibit while training.

The above photo was captured about half way through deployments of pairs, so you’re seeing a mix of rangers who have been picked up from deployment and those about to start their month out in the bush.

Regardless of where these guys were headed, the spirits were high and vibes were good. They were relaxed, and they were confident. There was singing, messing around, and plenty of laughs. From the outside looking in, it was clear that these men are a cohesive unit, with order among the seeming chaos.